Sept 18-20, 2024:

Nolan’s 14 consists of climbing/hiking/running fourteen of the 14,000’+ mountains in Colorado’s Sawatch Range in one foot-powered push of less than 60 hours. The exact route is open, but distance is about one hundred miles and elevation gain is around 45,000′. I learned about Nolan’s last fall and made the decision to do it early this year. Most people that attempt Nolan’s spend several years or more on the project. My hasty decision left me with little time to prepare.

I chose this challenge as part of my 60th birthday celebration to do one epic challenge each month of my 60th year. Nolan’s 14 is my 10th challenge this year. What caught my eye was the 60-hour time cutoff for my 60th birthday. As I began my scouting trips this summer to each of the mountains, I quickly realized how difficult that 60-hour cutoff would be. However, Andrea Sansone and Andrew Hamilton, the current record holders (of multiple things individually and as a couple) planted the seed of how beautiful the route is and to just stick with it no matter how long it takes and “do the line”. I liked the sound of that!

I am thoroughly exhausted after my attempt. Nothing has ever tested me to the degree this challenge did. I consider epic giving it 1000%. Nolan’s 14 was epic x 5.

It was a hectic summer of training, scouting and plenty of epic adventures per month (9 others). Notable adventures leading up to Nolan’s 14 were the Mountain Man Invitational (an ironman distance off-road triathlon at 10,000′ elevation) in August and the epic VaporTrail 125 mile mountain bike race in September. I spent considerable hours this summer dedicated to swimming and cycling workouts, and not quite as much on foot as I needed.

Nevertheless, only 10 days after VaporTrail125, Johnan dropped me off at Blanks Cabin, a trailhead on the south end of the Sawatch 14er mountain range. It was 2:15 am when I said my goodbyes to Johnan, Howie and Gracie (our two rescue dogs) and took the first step of many into the darkness of the tree covered aspen grove.

It was the night of the Supermoon (Harvest Moon) in September, and the Denver CO meteorologist, Chris Tomer, had kept me updated on the 3-day weather window before our first fall snowstorm that would leave significant accumulations of snow in the high country. I did not want to be up in there in those conditions trying to complete my challenge.

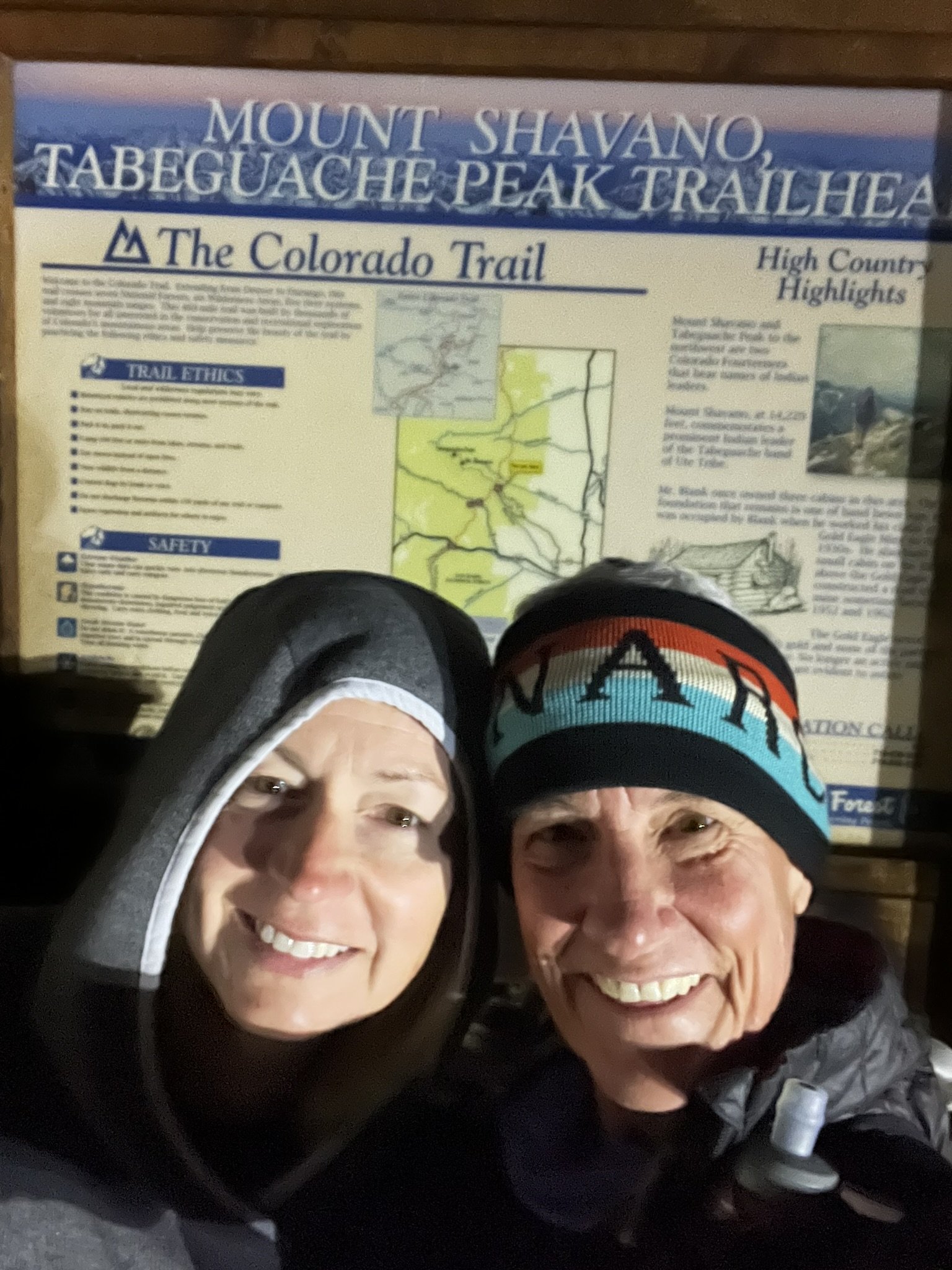

So, there I was in the darkness, full of excitement about having the moon to help light my path at night, and full of nervous anxiety for attempting the biggest challenge of my life. As I made my way up the flanks of Mount Shavano, I was giddy. I had trained for this all summer (some train for Nolan’s 14 for years because there is so much scouting of off-trail routes). I am lucky that I live locally to the Sawatch range since I could do some scouting each weekend. Ready or not though, I wanted to go this year.

The summit of Shavano was windy and dark. I used the most direct route, which leaves the main trail and heads straight up the mountain to the summit. The forecasts for my 3-day window were 25-50mph wind gusts for the summits, and temperatures ranging from 19/49F. I worried most about the wind. Being blown around on the ridgelines with a pack on your back is not fun, especially in the dark. Johnan reminded me; the wind is there to support you (never a negative thought). I have experienced that no matter how good you feel, just one negative thought can bring you down faster than any physical barrier. She knows that and was sure to keep positive thoughts in my head.

I hunkered down behind a rock, made a short video, and then set my sights on Tabaguache Peak. The moonlight lit Tabaguache up well, and I descended quickly to the saddle between Shavano and Tabaguache and made the short climb to the summit. I witnessed a most spectacular thing and shouted aloud the name “Tabaguache”! The sun was rising, and the full moon was setting, it was calm, and I felt the presence of my dad. I sat and soaked it in, knowing that no matter what else came of this adventure, I had just witnessed an incredible show. The light dusting of snow between the two mountains shimmered in the sunrise/moonset, and I snapped a picture. These two mountains are closest to my home and heart, and they both made me feel at ease up there. I was no longer afraid of the descent off Tabeguache, and made a quick hustle to the saddle, traversed toward Jones Peak, and descended the northwest flank being sure to stay out of the “nasty gully” that I had used before when scouting and feared for my life.

I was warm now that the sun was up, and I stopped at Brown’s creek crossing to filter new water for the climb up Mount Antero. My filter was terribly slow (perhaps slightly frozen from the chilly night). It seemed like I was there a long time getting enough water to fill my flasks and bottles.

Mount Antero is unique in that there is actually a 4×4 road that can be driven to within 500′ of the summit, but that road is much longer. I had a choice to make – take the road or follow the more direct route up a gully and over to a saddle and head straight to the summit from there. I was not particularly tired, so I decided to take the most direct route. I had scouted this route once, and there was nothing hard about it.

I hiked a short distance up the road and veered off for the gully. About two hundred yards up the gully, I decided to check my navigation to make sure I was on track. When I looked, I was surprised to find out I had turned one gully sooner than the gully I had previously scouted, and I was now in a gully that was used by David Hedges last year. I had downloaded David’s route because he broke the record for supported men and currently holds the FKT (fastest known time). His route managed to shorten the 100-mile route to eighty-nine miles by taking some aggressive straight lines (up and down). I did not feel I could follow his lines, because most are too steep or too technical for me, but I wanted to know where he went, just in case the line looked “ok.”

I was two hundred yards into this new line (for me), and going back down was not something my mind wanted to do. I have never enjoyed “out and back” courses, but rather seek out places I have not been before. My brain continued to move up this new line, and my body followed. Soon, one foot in front of the other, I was at the top and found myself grinning as I shuffled over the now seemingly flat terrain just beyond the saddle, making my way toward Antero. I was proud of the line I took, and I was now standing at the top of Mount Antero.

I was alone again for the third summit of the morning, and I took in the views of Mount Antero. On my way down, I exchanged words with a hiker headed up the last five hundred feet, asking me if it was even windier at the top. I assured him the summit was calm, and the high winds he was facing would be on and off as he made his way up.

Once at the saddle, the aquamarine mine appeared closed for the winter, and the access to the back side of the mountain was open (the shorter way down). I descended this shorter, albeit rocky road until I arrived at multiple switchbacks. Here I headed straight down the gully the most direct route to the creek at the bottom. I was running slowly (shuffling), as the soles of my feet were tender at this point and was listening to a podcast. A guy ran by me from behind on this section of road and scared me; I did not hear him coming. I crossed the creek behind him and stopped to filter water. A girl came down the trail behind him and they unlocked their bikes from a nearby sign. I asked if they had made it to the summit of Antero and he said, “No, we got a late start this morning.”

They pointed their mountain bikes down the same jeep road as me toward County Road 162. I knew Johnan and the pups were waiting at the bottom and was anxious to get down and start for Mount Princeton while the sun was still directly overhead. I needed plenty of time on the Class 3 crux of the Nolan’s line, a ridge I had scouted not too long ago and knew I did not want to be traversing in the dark.

My mood was impatient when I arrived at the truck. I wanted my light plugged in and charging even though I had used the moonlight most of the night. I snapped that the light charging status was not the right color. In my head it should have been red, but it was green. I kept unplugging it and re-plugging it in. Johnan refilled my pack with the nutrition I had listed on my spreadsheet. Howie and Gracie sat in the backseat of the truck and watched the comical proceedings. Johnan gave me a turkey, Havarti, avocado sandwich on sourdough from Sweetie’s in Salida. It was amazing, but I could only eat half of it. I wish I had taken the other half with me but was worried about the added weight in my pack.

My pack was around twelve pounds with my water in it. That may sound lightweight for a backpacking trip, but I felt was too heavy for a Nolan’s 14 attempt. 8-10lbs would have been better, but because of the weather pattern, I needed all my winter layers, plus first aid kit, emergency bivvy, battery brick for charging and my GoPro camera accessories. Capturing the beauty along my journey was important and I knew I was not going to be setting any records anyway. Note to self – I need more core workouts before next year, as well as side-hilling repeats. Maybe I’ll even just walk around our cabin wearing a pack for most of the day.

I left the comfort of Johnan and turned my thoughts to Mt Princeton via Grouse Canyon. A short hike through a historic cemetery took me up to the Grouse Canyon trail and I soon found myself in the heart of the baby aspens that have regrown after a recent avalanche. The leaves were changing color, and it was gorgeous.

I started this leg with only 1.5 liters of liquid, with the intention of refilling at the last creek before leaving tree line and getting up on the Class 3 ridgeline. When I arrived at the creek, it was dry. I had never crossed this creek when it was dry before (two previous times), and I felt a sinking feeling. I noticed on a downloaded route there was a confirmed water source up higher on the creek, so I hiked a slightly different route than normal up to the dropped pin for water on my map. Oh no…it also was dry!

At this point I decided to start rationing my water, knowing I had at least 3 hours total on the Mt Princeton ridgeline (2 hours on the way up and perhaps 1 hour on the way down before hitting water again). I saw a herd of mountain goats just before I climbed to the start of the ridgeline. They dropped over a saddle before I got to them, which I was thankful for as I did not know if they would just camp out where I wanted to go.

The ridgeline is long, and it seemed forever before I would be there. It was windy, and I stayed low in spots where the gusts came over small saddles on the broken ridgeline. I arrived at the Class 3 crux, and I picked my way around it. I could not remember the exact way I went before on a scouting trip, and I referred to my map what felt like every 60 seconds.

Even with rationing, I had run out of water near the summit of Mt Princeton; it had gotten dark on the ascent and the moon was not up yet. I knew there was water within 1-1.5 hours if I descended the most direct and shortest route that I had scouted twice previously to Maxwell Creek, though I had also felt very “unsafe” on those two descents and spent some time crab walking down where the rocks were quite loose (once in a light rain and once in dry weather).

I made the decision to “feel safe,” remove stress, and descend the standard route. The standard route was a LOT further, and I did not know when I would hit water again, but at least I would be moving downhill on stable ground, and this was what my body needed now to recover. My legs needed to recover for tomorrow which would be a solid sweep of five mountains at once. I temporarily satisfied my thirst by drinking my Embark Maple Syrups that I had in my pack, sucking on my cough drops from my throat that was now raspy, and eating a Maurten bar because I was also hungry.

I had forgotten how rocky the standard route was on Princeton, and though my intention was to recover, the top section was everything but recovery. At one point I had let my guard down, I caught my toe on a rock, and it sent me flying forward spread eagle. To avoid a faceplant, I curled up into a ball and summersaulted, launching myself off a small ledge about five feet high. My pack landed on the rock and snagged on something, bringing me to a halt just before my feet hit the ground below the ledge. I hit my hip hard on the rock, and that impact took the sails out of my wind. I received a nice scrape and bruise on my left hip bone.

At that moment, I felt the presence of a friend of mine, Dave Boyd, who had passed away on Little Bear Peak from a fall. He was alone at the time and on his third 14er of that day, and no one knows why he fell. It could have been a scary lightning strike, or something as simple as what I just did that sent him down the mountain. It was a reminder to never let my guard down again, and to make sure I got safely down from this challenge. Even though I stare at these mountains out my window every day and they seem so close, you are indeed far from any type of rescue help should something go wrong.

Once down the rocky section of trail, I descended a 4×4 road to a radio tower and then a few more miles to the Colorado Trail. Then I hiked another 7-8 miles more on the Colorado Trail before I got to Johnan. This section was long, and I did not get to water until a few miles into the Colorado trail. My mouth was dry, and my body was devastated. I spent time at the creek rehydrating and topping off. I constantly moved around and turned my headlamp from side to side, looking for any animals that might be lurking in the dark to attack their prey. I started talking aloud, to myself, but also to any animal that might be listening, trying to make myself sound like more than just one person.

I was down around 9k feet elevation now, and I had cell signal. I texted Johnan and she said, “I’m hiking in to meet you.”

That lifted my spirits which were low at this point. Mt Princeton had chewed me up and spit me out. I consider it one of the most majestic peaks of the route, and it can be extremely rewarding at the top with the view of every ridgeline (it has many), but it also is one of the harder peaks and in the dark, left me temporarily defeated. As I walked, I often swerved and sometimes stumbled. I jackrabbit came running down the trail toward me out of the darkness. It scared me and made me scream out. It darted off the trail when I screamed. I must have scared the rabbit as well.

Soon, I needed to poop for the first time since I started. I looked to the left and saw two sets of eyes staring at me. This was enough to decide I could “wait” until later. Soon, I saw a headlamp headed up the trail toward me and it was Johnan. I was relieved to see her and get the hug that I had been needing for a while. She waited on the trail while I relieved myself, and then we descended to the truck where I could finally crawl inside and get flat in the backseat for a short nap. Johnan set the alarm for 2 hours later for the sunrise at 6:50am, but I could not sleep and got up at 6:30. In total, I slept about 30 minutes. I doctored my feet, put on new shoes and socks, and got back on the trail at 8am.

I hiked two miles up County Road 306 to the Avalanche trailhead. I felt wrecked and wanted to quit, but I felt better than I did the night before, so I kept moving. I filtered 2.5 liters of water at the Avalanche Trailhead creek before I started up Mt Yale on the Colorado Trail (there would be no water until airplane gulley).

I had scouted the Nolan’s route from this direction only once, but it was enough to know I did not want to take that direct route up the Hughes Creek gully I had ascended when scouting. It had taken me 5 hours, and I felt I could do better by staying on the Colorado Trail to the East ridgeline of Yale and then traverse across the ridgeline trail. I had not scouted this line, but it was a trail on the map, so how hard could it be? Johnan felt I could make it in less than 5 hours.

Actually, this ridgeline can be hard when you are tired. I have no idea if I would have felt better on fresh legs, but I can honestly say I do not want to see the East ridgeline again any time soon. It was long and hard. At one point, I cliffed out after climbing the steepest part of the ridge and not being able to drop off the other side. It took a while to pick my way back down and go around this section. I was in that one spot for 30 minutes and knew my dot would not be moving on the Garmin website. I hoped no one would notice.

A few hours later, I was sitting at the summit of Mt Yale, once again alone. I soaked in the view and looked across the ridgeline I would descend to the top of airplane gully avalanche chute. I was looking forward to this descent to see if I could do better than last time. I had plenty of water and time, and I knew exactly where a natural spring comes out of the ground in this chute.

Coming off the backside of Yale, I saw a black chair on the descent, and I could not figure out who would hike a black chair all the way up to 14k feet and just leave it. As I got closer to the chair, it disappeared into the rock, and I realized it was nothing more than an illusion.

As I made my way down the ridge, I saw a herd of elk or deer in the distance. They descended over a saddle as I approached. They were huge which made me think of elk, but they had white butts which made me think of deer.

My toes hurt as I descended the avalanche chute. I stopped to look back at the steepness of the slope, and I noticed the abominable snowman up on the ridgeline. He was huge and motionless, and he was staring back at me.

I continued descending and felt his presence. I glanced back at him again, and my feet went out from under me. Shortly after that I started coming across various airplane parts that have been strewn about this gully after a 1956 small plane crashed killing all twelve people on board. I took pictures and video of airplane parts, and it seemed like every time I got my camera out and snapped a pic or video, my feet would go out from under me, and I would fall. I glanced up at the Yeti and could not help but wonder if he was the “keeper” of this gully, and that he did not particularly care for people to document things. I was tired of falling, so at this point in the descent, I stopped taking video.

I passed the natural spring where fresh water bubbles out of the ground and forms the creek, but knew I would be at the creek below within an hour, so I kept moving. The next section was the nasty remnants of an avalanche, and picking my way through the downed, snapped off trees was like a maze. I tried to follow my route from scouting, but trees continued to litter my intended route. Eventually though, I dropped out below, right at the bridge and my rendezvous point with Johnan and the pups. They had hiked the 1.5 miles up from North Cottonwood Creek trailhead to meet me (vehicles could not get to where I was), and Johnan set up a tent for me and fed me a hamburger that she had managed to keep warm while hiking in to me.

It was still daylight, but I knew the next leg would be in the dark and included five mountains before I would see her and the pups again. I had seen Johnan three times during my first five summits, but now I would be out for much longer before seeing her again. My predicted time to cover this difficult section was 16 hours, but deep down, I was concerned and no longer on fresh legs.

Also, Johnan told me that she did not know if a friend that was planning to join me on part of this section was going to make it. That brought havoc to my brain. I was trying to process whether I was more concerned with doing all five summits alone, or if it was just the Columbia to Harvard traverse in the dark. Either way, it was a daunting task. She asked me what I wanted to do, and I said, “I think I just need to stay here a little longer and then I’ll go.”

Getting out of that warm tent with Howie and Gracie sandwiched around one side of me and Johnan on the other, keeping me warm, was one of the hardest moments of the challenge. Leaving comfort is just as hard as experiencing pain. This moment was harder than the decision I made at the top of Mount Princeton to descend the standard route.

A huge hug later and I had to leave my crew behind. It was 9:45 pm and I had started my off-trail hike up Columbia. The first mile was very steep, dark, contained loose scree, and baby aspens dotted the slopes. I tried a line I had not done before through the pine trees. Because, why not, at this point? I was soon cussing my selection as it became just as steep as the scree slope, but with the addition of downed trees that really slowed my progress (imagine trying to get over huge crisscrossed dead pine trees (stacked up like a spilled box of toothpicks) by straddling them while on a steep slope that is pulling you back down. Eventually though, I arrived at the mellower slopes and hustled up to the ridgeline. Other than the rough start at the bottom, I was encouraged by a shooting star and by the time I arrived at the summit, alone again, it was 2:30am. Of course I was not really expecting to see anyone anymore, as the summits were all vacant even in the daytime.

It was windy, and I hid behind the rocks to make a video. I glanced across toward Harvard, which was only 2.75 miles away, but through a tedious boulder filled drainage ditch that involved route-finding and boulder hopping. This was my third night out since I started, and the moon was now receiving cloud coverage off and on from a thin sheet of clouds that was moving in from the approaching snowstorm in the forecast for next day. I used my light trying to find any signs of rock cairns to guide my way, and for foot placement. The light often threw shadows though, and I caught a glimpse of humping penguins just before I dropped off the ridge into the boulder basin. I stared at the penguins and turned my light off and on. They were still humping; I hiked on anyway.

This drainage ditch robbed me of valuable time because of the darkness. I felt I was going in circles, even though I wasn’t. My glute muscles were firing like never before. I could feel them growing in strength as I pushed off from boulder to boulder. It was such a contrast to feel my muscles getting stronger vs the feeling of getting weaker up to this moment. I deemed that very odd.

At one point, I saw a kayaker in the middle of all the boulders, and upon closer examination discovered it was a big slab of light-colored rock with a dark rock cairn on top. This was encouraging that I was on a “path” of sorts.

The sun began to rise around 6:45 am, and I was now just out of the boulders and on some more forgiving slopes leading up to Harvard ridgeline (over 4 hours after leaving the summit of Yale). This was discouraging, but another beautiful sunrise followed which made it worth the effort.

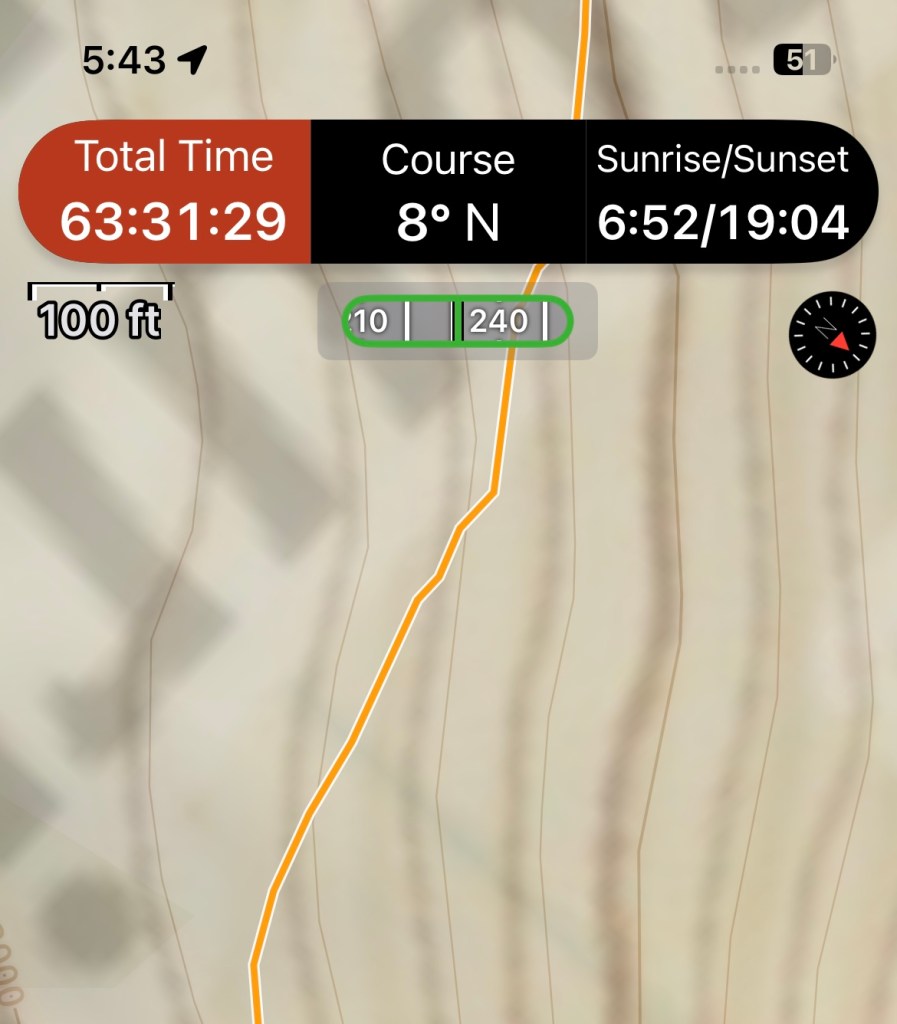

There was a much longer ridge traverse once I got up there than I had remembered. At 8:15am I arrived at the summit of Harvard. My spirits were down, as it had taken me over 6.5 hours to traverse something that should have been 3-4hrs. Yes, it was dark, but dang! I felt defeated again. It was summit #7, alone again, and just under 54 hours into my adventure. Harvard had made me work more than I wanted to.

Three hours later I was near the bottom of the Harvard descent, tramping through the forest undergrowth and downed trees. Animal tracks were everywhere, and at times I could follow the game trails. I could smell the animals in this area (elk or bear), and so I mentioned aloud that I was “just traveling through” and letting them know I was coming.

Shortly after, I found the creek crossing at Bedrock Falls. I slipped and fell into the creek (by stepping on a slippery rock to cross) and got both of my feet and socks completely wet. I lied down on the smooth rock slab of Bedrock Falls for a moment. The sun was directly overhead, so I took off my shoes and socks and placed them on the rock to dry.

Together, my socks and I soaked in the sun. I wanted to nap, but I was concerned about animals lurking in the vegetation along the creek. I sat upright on the rock instead. And yes, I did forget to bring a spare pair of socks, even though I had a spare pair of everything else in my pack. All my socks were with Johnan, and I was changing socks and shoes each time I saw her.

I filtered water and filled another 2.5 liters for the next three mountains (Oxford/Belford/Missouri). I applied blister aid to my feet. I waited 30-45 minutes, and though my socks made their best effort to dry, they came up a little short. I was closing on 60 hours, and I wanted to officially hit 8 summits within the 60 hours, but that meant having the climb of my life up Oxford if I was going to make it.

When I scouted Oxford, it had crushed me. I remember that day well as I had gotten dehydrated and had to descend Missouri Gulch coming off Belford, skipping my scouting of Missouri. Today I wanted a “redo.” Here was my chance to climb Oxford “off-trail” and have enough hydration to make it to Missouri before descending to Johnan, the pups, and Darren (a life-long friend) who was also now waiting on me and was going to join me on Huron.

I headed up Oxford and saw a pair of llamas. The owners had tethered the llamas to stakes in the ground but the owners were not present. I figured they were out hunting. I thought about that often as I hiked up the “off-trail” gully, hoping if they were hunting that I did NOT look like an animal. I had caught a second wind and ascended Oxford faster than my scouting trip. I was within 45 minutes of making it by the 60-hour time cutoff, and I found myself wishing I had not fallen in the creek (even though it did feel good at the time). I needed that time back if I was going to get eight summits in 60 hours.

There were two guys on top (for the first time, people!). I made a video before arriving at the top since I was in the comfort of the rocks below where there was no wind. Once on top, the wind was whipping, and the two guys were hunkered down in the only summit rock shelter, so I said hello and kept moving.

It took about an hour to traverse across to Belford, something that normally takes me 30 minutes to do. Once again, I felt slow here, and was now feeling the effort I had put forth going up to Oxford. I had turned myself inside out, and I was paying the price. The two guys passed me as I shuffled along, and they made it up the ridge toward Belford 20 minutes ahead of me. One stood in victory with his arms above his head. I ached to be up there, and I counted the minutes behind I was when I arrived at the same location. Along this traverse, I started rationing my water again, talking aloud to imaginary friends that I was saving the water for. I said to one, “I’ll just have a little sip to wet my throat, but not too much, I know you will need some later.”

On top of Belford, I glanced over at Missouri mountain and remembered I had not scouted the trail I was planning to take on the backside of the mountain. I had downloaded that from Justin Simoni’s website, and I just needed to get down to Elkhead Pass and then pick up that trail on the backside. I had 2.5 hours before sunset, so I didn’t stay long on Belford.

As I headed downhill, my toes started screaming. Descending was no longer something I looked forward to. At the pass, I scanned the Missouri mountainside for the trail on my map but found nothing. Not surprising, as they are often hard to see in the rocks until you get there. As I got closer and pulled out my map it was obvious there was no trail.

This meant side-hilling all the way across the steep slope of scree to the other side where there was a small saddle at the top to access the ridgeline. I was delirious by then, and not clear about how many miles of side-hilling it would be. I was excited to see a man and his dog on this trail, only to realize as I got closer it was just another illusion within the rocky slopes. I felt a sense of urgency to make it to the saddle before sunset.

Once again, I turned myself inside out to make it across the slope, and oddly enough while rock hopping, I was getting a weird sensation of a foot massage. I was not going to knock it, because it felt the best my feet had felt in quite a while. My heart rate was elevated but I embraced the imaginary path and held myself at the same contour line on the topo map until I could see the saddle above me. I hiked straight up the rocky scree to gain the ridge.

This was just minutes before sunset, and I applauded myself for being able to video the sunset and arriving at the summit before the mountain had gone dark. I had done it – 10 summits that is, in one push, and five alone on this last segment, by myself with a huge chunk being in the dark.

I felt warm inside and soaked in the last drops of the sun before darkness set in. I had no idea of what awaited me. This was the section of Missouri I had not scouted thinking it was a straightforward trail. However, instead of straight forward it was straight downhill; there were no switchbacks. I cussed the maker of this trail, and questioned aloud multiple times, “What were you thinking? You must have been wanting no one to ever hike this trail more than once. I know I will not. I will be looking for a different route next time.”

It was hell. In fact, I did cry on this section. The questions rushed out of my mind into the night air, “Why is this so steep? Why can’t anyone see my headlamp up here? Why are all these rocks in the way? Why can’t there be switchbacks? Surely this will level out soon. What the hell? Where is the f***ng lake, where is my crew, why can’t they see me? What is that – a black panther? I see you over there in the tall grass. I am not afraid, if you want to kill me just do it. It is better than the death of walking down this steep trail. Oh, you are not a panther? Let me turn off my light and turn it back on and see if you are still there. You are! I knew you were real. Listen I am going to keep walking and leave you behind. You stay there, and I really do not care. You do not want to mess with me. Oh, anyway, I see your friend now. I see you Mr. Marmot, standing tall out of your hole. Oh, I am sure you too are trying to trick me and are really a rock. Watch, I will turn my light off and back on and you will still be there. Nope! OMG you are gone. You were real and went back into your hole to hide. I am just passing through, and who built this trail anyway? It sucks.”

This outward talk lasted the entire rest of the way down. I was exhausted, was low on water again and in my brain, I was in rationing mode. I ate a piece of chocolate to calm my scratchy throat, and I vomited a piece that got stuck in my dry throat. I drank more water and spit out the chocolate remnants. Once again, I was a mess, and I told myself I was going to get all this out before seeing Johnan and Darren. The trail eventually ran into the creek that feeds Clohesy lake, but I quickly got “off-trail” when it just disappeared into the brush and downed trees.

“Where is the lake,” I yelled, “where is everyone? This trail is messed up. I hate it. Why are there so many misleading rabbit holes that take you nowhere?”

Eventually I staggered into camp where my crew was at 9:30pm (2 hours from when I left Missouri summit). At last, they saw my light with thirty feet to go. Johnan came to give me a hug, and even though she had set up a tent for me to rest and recover in, all I saw was the backdoor of the truck and I crawled into the two dog beds, my head in one and my legs draped over into the other. I do not know what Gracie and Howie thought about this, but I did not care, and they didn’t seem to either. They scooted over and tried to make room. It was not like their beds were going to make me smell any worse than I already did.

Johnan told me if I did not get back on trail for Huron by midnight then I could not go out because of the snowstorm due to arrive the next day at 11am in the high country. My feet were toast and when I took off my shoes and socks, Darren told me, ” That blister is a good one!”.

I did not look and did not care. I had maxed out and knew the next segment (if I went out) would involve crawling. It did not take long for me to express that, “I was done.”

Darren said we could hike Huron another day together, and I agreed whole heartedly. I was not disappointed to stop, because I felt like on that day and at that time, I was maxed out. I had given it 5,000% effort and had nothing left to give. I was on my way to accomplishing my 60th birthday wish – to do one epic challenge a month for 12 months, with this one being the highlight of the year for month #10 and 10 x 14er summits.

So, I pulled the plug and stopped for the night. Johnan and Darren packed up the tent and all our gear. We rocked and rolled down the technical 4 x 4 (a 2-mile stretch but it took an hour to drive down). A person could walk down the road faster, but I took solace in the fact that I was being jostled around in the back with the dogs rather than crawling up Huron right now on my hands and knees.

I was amazed at how quickly my body went into recovery once my brain decided it was time. I was moaning from the knee pain that had immediately set in once my brain realized I was stopping. My hamstrings joined in the misery and started cramping. Also, during the hour drive down, I had Johnan stop so I could pee. I must have left a quart of liquid behind; it was the longest pee I had since starting three days earlier. I could not believe it.

I developed what sounds like a “smoker’s cough,” but it is just the aftermath of the exertion at altitude. It is almost gone now, and my lungs are clearing up; it lasted about a week. Even my hip bruising is gone, and all that remains is a tiny scab where I hit the rock. I learned so much on my attempt at Nolan’s 14 that after some rest, I might be able to make the conscious decision to give it a whirl again next year. The fact that I even thought about this on the drive home made me realize how likely that is to happen. But before I make any drastic decisions about next year, there will be more rest, life, love, and landscaping.

Trip stats:

Recorded with Coros Vertix 2S

Start 2:14am, September 18, 2024 at Blanks Cabin, San Isabel National Forest, Clear, 40 degrees, Feels like 29 degrees, Humidity 56%, Wind 9.8mi/h from SW.

64 miles

67:25:02 hours

34,186 feet elevation gain

7 fourteener peaks before the 60-hour cutoff

10 fourteener peaks total (Shavano – Missouri) South to North, Supported at road crossings by Johnan and our pups

Many thanks to:

Johnan Ratliff – the do everything support crew while working full-time. You are simply AMAZING and a constant reminder of what love is, and that I am loved.

Gracie & Howie – your warmth in the tent and your spirit on the ridgelines comforts me.

7000’ Running Store in Salida – for believing and supporting

Andrea Sansone & Andrew Hamilton – thanks for encouraging me to just “do the line”

Ascent Eye Care in Salida – for getting my custom Oakley’s fit and sized on short notice

Basecamp – for the last 4 years of base building, for reminding me of my courage and strength to explore, and for the mantra – that if you have a passion greater than your fears, it is all possible!

Brian Passenti , Coach, Altitude Endurance Coaching – the notion, the nod, and the nudge

Carolyn Chambers – my amazing boss, leader, and enabler to realize my full potential

Chris Tomer, Meteorologist – keeping me safe up there

Coros – for a watch that can outlive my activities

Darren Lacroix – making the road trip up to Clohesy Lake to meet me for Huron when I would be feeling my worst

Emily at Boulder Longevity – for keeping my nutrition, longevity and healthspan on point

Sam Piccolotti – strength training

Family & Friends – thanks for following along and all the prayers

If you enjoyed the read – here is my You Tube video link of the video footage I captured on my GoPro and iPhone. I’m not a great videographer, but I’m learning: https://youtu.be/OHVmxbK4kOE

Podcast Episode #37 Listen Buckle Up with Simon and Brian: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/ep-37-with-kathy-duryea/id1729238599?i=1000673192942

Podcast Episdoe #37 Watch on You Tube Buckle Up with Simon and Brian: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-4G-S5Bcxvg&t=30s

Leave a comment